Beyond Oil: How a National Pipeline Can Secure Canada’s Economic Future Through Diversification

Canada’s pipeline strategy aims to secure a diversified, resilient economy by reducing inflation risks, expanding global market access, and sharing wealth across provinces. Inspired by Norway & Australia’s successes, it's a blueprint for a stronger, more united Canada.

Pipelines, Inflation, and Prosperity: A Canadian Story of Diversification

Setting the Stage: A Pipeline Plan for a Stronger Canada

Imagine a pipeline stretching from Alberta’s oil sands to Canada’s coasts, with every province getting a slice of its profits. This is the vision behind a proposed transnational pipeline strategy with interprovincial profit-sharing. It’s pitched as a nation-building project to tame inflation, dodge tariff risks, diversify the economy, and boost Canada’s competitiveness on the world stage. In 2025, Canadians find themselves grappling with rising living costs and heavy reliance on one big customer (the U.S.), so this pipeline idea comes at a pivotal moment. Can a big piece of infrastructure really help keep prices in check and strengthen our hand in global trade? Let’s unpack the economic concepts and real-time data behind this bold strategy, in plain language and through a few stories, to see how it all connects.

Key Concepts: Inflation, Tariffs, and Concentration Risk Demystified

Before diving into pipelines and profit-sharing, we need to clarify three economic concepts:

Inflation

Inflation is simply the rate at which prices for goods and services rise over time, reducing what your dollar can buy. In other words, inflation means too many dollars chasing too few goods heritage.org. If demand outstrips supply, say everyone wants lumber but mills can’t produce enough, prices go up. Conversely, if there’s plenty of supply (or not enough money circulating), price increases slow down bankofcanada.ca. Think of it like a classroom auction: if the teacher hands out a lot of play money to students (more money in circulation) but doesn’t increase the number of candies to bid on (goods), the “price” of candy will shoot up. Inflation in Canada is measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and keeping it low and stable (around 2% per the Bank of Canada) is crucial so that paycheques and savings don’t lose too much value each year bankofcanada.ca.

Tariffs

A tariff is a fancy word for a tax on imports (or sometimes exports). If country A puts a 20% tariff on steel from country B, it means any steel B sells to A faces an extra 20% tax at the border, making it more expensive in A’s market. Tariffs are often used to protect domestic industries or as bargaining chips in trade disputes. For consumers, tariffs can mean higher prices (because imported goods cost more). For exporters like Canada, being exposed to tariffs, especially from the United States, our biggest trading partner, is a risk. A sudden U.S. tariff on Canadian goods (steel, aluminum, softwood lumber, or even oil) can hurt Canadian producers and workers by pricing them out of the market. We saw this risk in action when the U.S. imposed tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum in 2018, and again in 2025 where a newly elected U.S. president slapped tariffs on Canadian imports (more on that later). The key is that tariffs can quickly change the flow of trade and who pays what, so reducing “tariff exposure” means finding ways to not have all our eggs in one basket, i.e. not relying on selling to just one country.

Concentration Risk

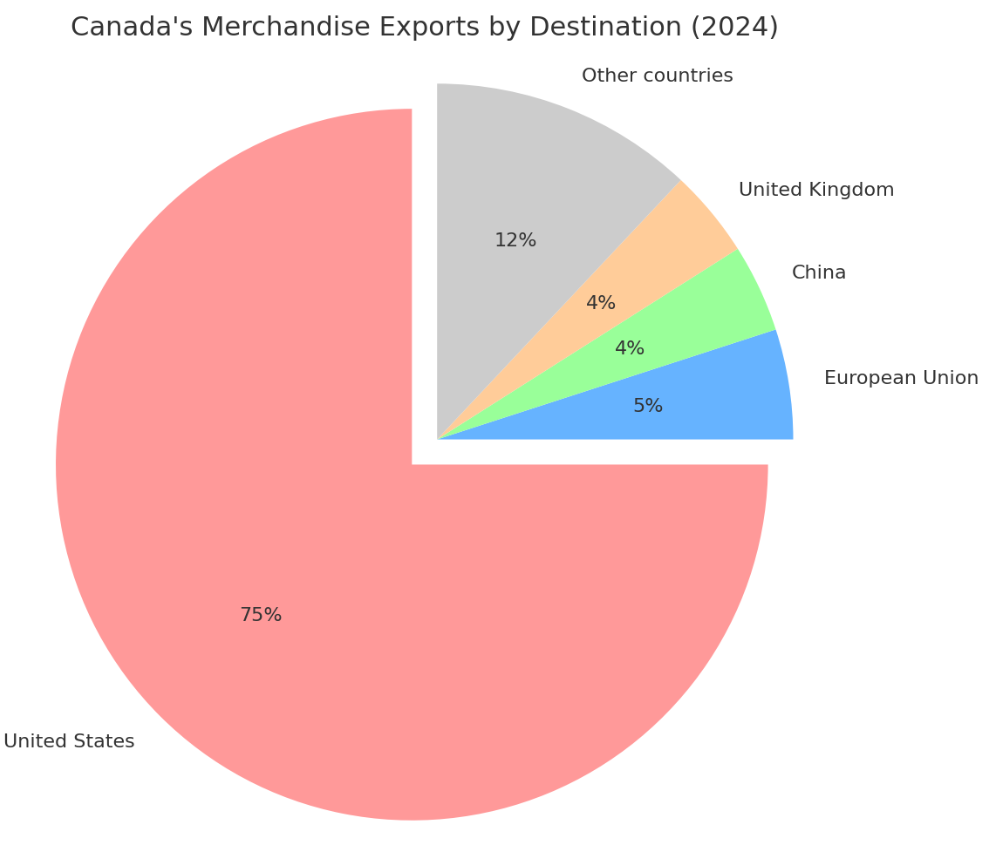

This is a concept borrowed from finance and ecology, basically, don’t put all your eggs in one basket. In economic terms, concentration risk means over-reliance on a single market, commodity, or sector, so that if that one thing has trouble, the whole economy feels the pain. Canada faces concentration risk in two big ways: sectoral and geographical. Sectoral, because a large chunk of our exports (and a good share of our economy) comes from a few natural resources, oil being a prime example. Geographical, because an overwhelming portion of our trade is with one partner: the United States. It’s like a farmer who only grows one crop, if that crop fails or prices crash, they’re in trouble. In Canada’s case, if the U.S. market sneezes (or raises tariffs), we catch a cold. How concentrated are we? As of recent data, about 75% of Canada’s merchandise exports go to the U.S. investorsfriend.com. That’s an enormous share, by contrast, no other single country accounts for more than 5% (the entire European Union is ~5%, and China and the U.K. about 4% each) investorsfriend.com. You can see this imbalance vividly in the chart below, where the big pink chunk is the U.S.:

Canada’s export destinations are heavily skewed to one partner, the United States (75% of exports), illustrating a concentration risk investorsfriend.com. “Other countries” include all remaining trade partners, none individually above a few percent.

Concentration risk also appears in what we export. Canada is known for exporting commodities: in 2024, crude oil (and other energy products) made up roughly 18% of our exports, the single largest category investorsfriend.com. Add other natural resources like metals and minerals, and a large portion of our export earnings come from stuff we dig or pump out of the ground. There’s nothing wrong with having strengths, Canada is blessed with resources, but it does mean we must manage the risk of dependence. If oil prices tank or if our one big buyer doesn’t need our oil, the economy takes a hit. That’s where diversification comes in, a recurring theme in our story.

Now that we have these concepts down, inflation (prices rising), tariffs (trade taxes), and concentration risk (too much reliance on one thing), let’s see how they play into Canada’s current economic situation and how a pipeline might matter.

Canada’s Economic Snapshot in 2025: The Numbers Behind the Story

To ground our analysis, let’s look at the real-time data on Canada’s economy as of 2025:

GDP Composition

Canada’s economy is dominated by services. About 70% of Canada’s GDP comes from the service sector, everything from banking to health care to tech to retail statista.com. Roughly 22% is from industry (manufacturing, construction, energy, mining), and only around 1-2% from agriculture statista.com. In other words, the vast majority of Canadians work in offices, shops, hospitals, schools, etc., not in oil fields or wheat farms. However, our natural resource sector, though only ~5% of GDP by output investorsfriend.com, punches above its weight in exports and in certain regions’ economies. For example, the oil and gas industry (within that 5%) is huge for Alberta’s provincial revenue and makes up about one-third of Canada’s export earnings by value (especially after the oil price surge in 2022) economics.td.com. So, Canada is a service economy with a resource engine under the hood. It’s like a hybrid car: most of the time you run on the regular engine (services), but when you need a boost, the resource sector’s like the turbocharger, with all the hazards of running hot if not managed carefully.

GDP Size and Growth

Canada’s annual GDP is about $2.2 trillion USD (≈ $3.1 trillion CAD) as of 2024 investorsfriend.com. We experienced a strong post-pandemic rebound in 2021, slower growth in 2022 - 23, and are looking at modest growth ~1.5 - 2% in 2025 according to the Bank of Canada bankofcanada.ca. Not stellar, but steady, however, this outlook assumes no major disruptions like new tariffs or recessions. That’s one reason the pipeline strategy appeals to some: it’s a potential new growth driver and insurance against shocks.

Inflation Rate

Canadians became painfully aware of inflation in the past couple of years. After decades of mild inflation ~2%, we saw a spike in 2021 - 2022. Inflation peaked at 8.1% in June 2022, the highest in nearly 40 years statista.com. This was due to a perfect storm: pandemic supply chain snarls, surging oil and food prices, and yes, a lot of stimulus money sloshing around. The Bank of Canada responded by aggressively raising interest rates, and by 2024 inflation cooled off. In fact, inflation eased to about 1.9% by January 2025 www150.statcan.gc.ca, right back in the Bank’s target range. The latest reading (Feb 2025) ticked up to 2.6% year-over-year www150.statcan.gc.ca, partly due to the end of some temporary tax rebates, but generally we’re around that 2% sweet spot bankofcanada.ca. So as of 2025, inflation is technically under control. But Canadians still feel the after-effects (prices are 8% higher than in 2021 on average), and there’s a lot of anxiety about it flaring up again. The pipeline strategy promises to help on this front by improving supply efficiency, we’ll examine if that holds water.

Export Distribution & Trade Dependence

Canada is a trading nation, exports are about 30% of our GDP (around $700 - 800 billion CAD a year). And as mentioned, about 3/4 of those exports go to the United States investorsfriend.com. The U.S. is by far our largest customer, particularly for energy, cars, and lumber. For example, Canada sends about 97% of its oil exports to the U.S. cer-rec.gc.ca under current pipeline constraints! This tight linkage means our fortunes are tied to American demand and trade policy. On the one hand, integration with the giant next door brings efficiency and wealth (hence the long-standing NAFTA/USMCA free trade deal). On the other hand, it creates vulnerability, a lesson driven home when U.S. politics turn protectionist. To visualize this, refer again to the export pie chart above: if the U.S. slice shrinks due to a tariff, can we quickly grow the other slices? Not without infrastructure to reach other markets, which is exactly what a coast-to-coast pipeline could provide.

Tariff Exposure Example: In early 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump (in a return to office) announced tariffs on Canadian and Mexican goods. Canadian oil was hit with a 10% tariff (versus 25% on other imports) reuters.com, a slight “break” recognizing how dependent the U.S. itself is on Canadian energy. Even with a smaller tariff, this sent shockwaves through Ottawa because it underscored our tariff exposure. Canada supplies 50% of U.S. crude oil imports reuters.com, and 70% of the feedstock for U.S. Midwest refiners comes from Canadian heavy crude reuters.com. In turn, 90% of Canada’s oil exports go to the U.S. market reuters.com. In short, both countries are entangled in this energy trade. The tariff threat illustrated a key point: Canada’s lack of alternative export routes forced our producers to accept a lower price (Western Canada Select crude’s discount to U.S. oil widened further) reuters.com to keep U.S. buyers interested under the tariff. It’s a vivid case of how concentration risk and tariff exposure can team up to bite. Canada’s theoretical escape hatch? Having pipeline access to tidewater, meaning the ability to put oil on a ship and send it to Asia or Europe, bypassing any U.S. tariff wall reuters.com. This real-time drama makes the case for diversifying our trade routes, a major rationale for the proposed pipeline.

With this snapshot in mind, the stage is set. We have a solid service-based economy with a significant resource component, low inflation (for now) after a scare, and an export profile that’s lucrative but highly concentrated in both product and destination. Now we’ll examine how a transnational pipeline with profit-sharing could impact these elements, inflation, tariffs, diversification, competitiveness, and compare it with approaches in Norway and Australia.

Fighting Inflation with Pipelines: Supply Chain Efficiency vs. Monetarism

Can a pipeline really help tame inflation? It might sound odd, after all, inflation is often seen as the domain of central banks and interest rates, or as Milton Friedman famously put it, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” heritage.org

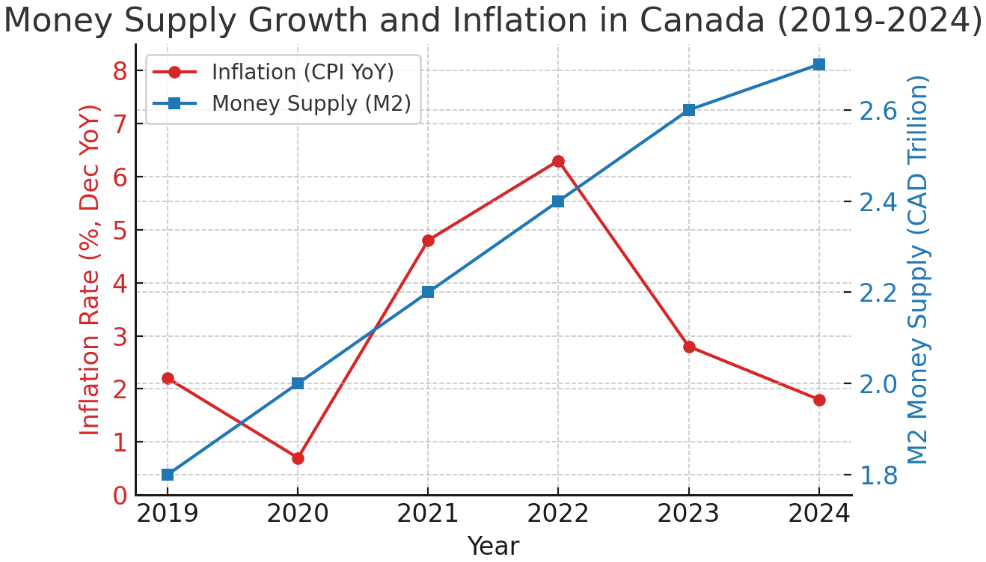

Friedman’s monetarist theory holds that if the money supply grows faster than the economy’s output, prices will inevitably rise. By that logic, the cure to inflation is tightening the money spigot (higher interest rates, less money printing). Canada followed this playbook in 2022 - 24: the Bank of Canada hiked rates sharply, money supply growth stalled, and inflation indeed came down. The red line in the chart below shows the inflation rollercoaster, and the blue line shows Canada’s money supply (M2) over recent years:

Canadian inflation spiked as money supply surged post-2020, then subsided as monetary growth slowed. Monetarists like Friedman emphasize this correlation heritage.org. However, supply-side measures (like improving infrastructure) can also influence inflation by affecting the availability and cost of goods.

Friedman wasn’t wrong, too much money chasing too few goods will cause inflation. But that phrase has two parts: money and goods. Supply-side solutions aim to increase the “goods” or reduce the cost of getting goods to market. That’s where a pipeline comes in, as a form of supply chain infrastructure.

Let’s break it down in practical terms. Energy, gasoline, diesel, natural gas, is a major input cost for almost everything. When energy prices spike, the cost to ship food, to heat buildings, to run factories, all go up. This can trigger cost-push inflation (rising costs pushing up overall prices). If we can move oil and gas more efficiently and cheaply, we can alleviate some of that cost pressure.

A new transnational pipeline, say from Alberta to Eastern Canada (and onwards for export), can help in a few ways:

Reduce Transportation Costs

Pipelines are the cheapest way to move oil. Estimates show that transporting crude by pipeline can cost around $5 per barrel, versus $10-15 by rail forbes.com (and even more by truck). This huge efficiency gain means oil from Alberta could reach refineries or ports at a lower cost. Cheaper transport could translate to a couple cents less per liter at the gas pump than it would otherwise be, and large industrial users would save on feedstock costs. These savings, while not making oil cheap, can soften price spikes. When businesses save on energy and transport, they are under less pressure to raise their own prices horizonrecruit.com.

- Increase supply and reduce bottlenecks: A pipeline adds capacity. If previously the pipeline system was a chokepoint (leading to oil supply gluts in Alberta and shortages elsewhere), a new line opens the flow. For example, if Eastern Canada can get additional crude from Western Canada via pipeline, it might import less overseas oil. More stable domestic supply means less vulnerability to global price shocks. During the 2022 oil price spike, Eastern Canadians paid hefty premiums for gasoline partly because they rely on imports priced at global benchmarks. A pipeline could make supply more secure and possibly reduce regional price differentials within Canada. In economic terms, it can shift the supply curve to the right (more supply), exerting downward pressure on prices compared to the status quo.

- Efficiency and certainty: Infrastructure gives predictability. If goods can move smoothly, firms don’t need to build in “chaos costs”. Think back to the pandemic when supply chains were disrupted, prices for shipping containers, etc., went crazy. By investing in robust infrastructure, we reduce the chance of that kind of disruption-induced inflation. A pipeline is not a cure-all (you can’t pipe semiconductors or lumber, after all), but it addresses one critical sector. It’s one piece of the puzzle to keep the economy’s plumbing running smoothly.

Now, how does this compare to pure monetarism? Friedman might say: “If you want to stop inflation, just don’t let money supply grow too fast.” Indeed, Canada’s money supply (M2) jumped over 20% from 2020 to 2022, coinciding with the high inflation, and then its growth slowed to near-zero by 2023 as the Bank of Canada tightened policy, coinciding with inflation coming down. The chart above illustrates this relationship. However, what Friedman’s view doesn’t directly address is cost-push inflation. In 2021 - 22, part of our inflation was driven by supply shocks (like oil over $100/barrel, global logistics snarls). Even Friedman acknowledged that other factors can temporarily drive prices and that monetary policy works with a lag.

A pipeline is a supply-side measure. It targets the “too few goods” part of “too many dollars chasing too few goods.” By itself, it’s not enough to control economy-wide inflation, if the money supply went wild, a pipeline won’t save us. But as a complement to sound monetary policy, it can mitigate inflationary pressures. For example, if the pipeline reduces transportation costs, the price index will be lower than it otherwise would be for a given money supply. It’s akin to taking an umbrella and wearing a raincoat in a storm: the umbrella (monetary policy) stops most of the rain (inflation), but the raincoat (supply improvements) gives extra protection against the drizzles that sneak by.

Let’s also consider expectations. If Canadians see the government taking action to improve infrastructure and lower costs, it can anchor inflation expectations. When people believe inflation will stay low, it often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy (they don’t rush to beat price increases, which keeps demand steady).

Storytime: Think of two bakeries in a town, one has its own wheat field out back and a direct pipeline (a bit fanciful for flour, but bear with me) to get grain cheaply; the other relies on buying flour that’s trucked in from far away. If fuel prices skyrocket, the second bakery’s costs soar, and it raises bread prices; the first bakery, with its efficient supply, can hold prices more stable. Now scale that up to a country with oil. The pipeline is like our direct supply line, making us less at the mercy of external price swings. In the long run, stable input costs contribute to stable prices overall.

To summarize this section: Monetarist theory says control inflation by controlling money, and indeed Canada’s central bank will continue to do that. The pipeline strategy attacks inflation from the other side, by easing supply constraints and improving efficiency. It’s not contradicting Friedman, it’s complementing him. Milton Friedman would likely agree that if you can increase output or lower production costs, you alleviate inflationary pressure, he’d just emphasize that without sound money, those gains could be erased by an over-expansionary policy. The ideal scenario is to do both: maintain prudent monetary policy and invest in infrastructure that makes the economy more productive. The pipeline falls into the latter: a one-time investment that could pay ongoing dividends by making our supply chains cheaper and more reliable.

Diversifying Markets: Tariffs, Trade, and the Pipeline Path

When it comes to trade, diversification is Canada’s defensive and offensive play. As we saw, being tethered to the U.S. market is lucrative but leaves us exposed. A key promise of a transnational pipeline (especially one reaching tidewater) is that it can open up new export markets, reducing our vulnerability to U.S. trade policies and demand fluctuations.

Let’s unpack the tariff angle first. What does a pipeline have to do with tariffs? In simple terms, if you have more places to sell your product, you’re less beholden to any one buyer’s tariffs or whims. Right now, the U.S. knows Canada has limited capacity to send oil elsewhere (a few pipelines to the States, and a nearly complete Trans Mountain expansion to the Pacific which will help, but eastern outlets are lacking). This can create a power imbalance. The 2025 Trump tariff scenario was a wake-up call: even the threat of a tariff can force Canadian exporters to cut prices or lose sales reuters.com. Diversifying markets is like having multiple clients in business, losing one big client hurts, but you survive if you have others.

How would the pipeline enable diversification? If it’s an east-west pipeline to the Atlantic, it could feed refineries in Eastern Canada (reducing the need for imports) and crucially allow exports from an Atlantic port to Europe or beyond. If it’s a westward expansion (like the Trans Mountain Pipeline to the Pacific, twinned or another one), it allows more exports to Asia. Either way, the idea is Canada is no longer geographically bottlenecked into selling south. We could put oil on tankers bound for Europe, India, or other parts of Asia, chasing the best price and forging new trade relationships.

This has several benefits:

Leverage in Negotiations

If the U.S. knows Canada can sell elsewhere, the likelihood of harsh tariffs might decrease. In 2025, commentators noted that Canada “has the option of bypassing the United States” via the Trans Mountain pipeline system to the Pacific reuters.com. That option, even if not used to full capacity, gives us a bargaining chip. It’s similar to how having multiple bidders for your house can get you a better price, if one lowballs you, you can say “no thanks, I have other buyers.” For Canadian oil, more buyers means we’re less likely to be bullied on price or subjected to punitive measures without consequence.

Reduced Tariff Impact

If a tariff does hit, a diversified exporter can reroute goods. For example, when China slapped tariffs on Australian barley and wine in recent years, Australian exporters scrambled to find other markets in Asia and Europe. They didn’t replace all of the lost Chinese sales, but they mitigated the damage by diversifying. If Canada had a pipeline to Atlantic tidewater during a U.S. oil tariff, we could redirect some flows to Europe (which, incidentally, has been seeking stable oil supply from friendly nations post-Russia’s Ukraine invasion). Those European buyers might not take all our oil, but even taking a portion helps keep Canadian exports flowing and our industry running.

Market Competition = Better Prices

Right now Canadian heavy crude (Western Canada Select, WCS) often sells at a discount to world prices because of limited pipeline capacity and the fact it mostly has one buyer (U.S. refiners). In late 2018, a lack of pipeline space caused the WCS discount to balloon to over $40/barrel (cer-rec.gc.ca), a huge loss of value to Canada. With adequate pipeline access to multiple markets, this discount tends to shrink because more buyers compete for our barrels. Less discount means more profit and tax revenue for Canada, without raising consumer prices (it’s capturing value that was previously lost to inefficiency). More profit can be reinvested or shared (we’ll get to profit-sharing soon), and more tax revenue helps fund public services without borrowing, indirectly helpful for the economy’s health and inflation control too.

We should acknowledge that diversifying exports is easier said than done. Building new trade relationships takes time. Europe, for instance, has its own complexities (they are trying to transition off oil long-term, but in the medium term they needed non-Russian oil/gas urgently in 2022-24). Asia (like India, China, Japan, South Korea) is a growing market for energy, but Canadian exporters need to be reliable and price-competitive to gain a foothold. A pipeline to the Pacific (Trans Mountain expansion, “TMX”) is already slated to help here, when fully operational, TMX will allow about 890,000 barrels per day to flow to the British Columbia coast for export reuters.com. The government actually bought and expanded this pipeline precisely to improve market diversification for Canadian oil. Similarly, an eastward pipeline (often dubbed “Energy East” in past proposals) could send ~1 million barrels per day to Saint John, New Brunswick (home to a large refinery and port). Combined, these projects mean Canada wouldn’t be a captive supplier to the U.S. but a global player in oil markets.

Let’s illustrate concentration vs diversification with a quick interactive thought experiment. Prompt: Consider your own income, if you had a side gig in addition to your main job, losing your main job would still hurt, but at least you have something to fall back on. If that side gig grows, you might even have the confidence to negotiate better terms at your main job, knowing you’re not utterly dependent on it. Similarly, Canada having multiple export routes (side gigs) alongside the U.S. market (main job) strengthens our hand.

On tariffs beyond oil, diversification helps too. For instance, if we develop new markets for lumber in Asia, a U.S. tariff on lumber is a bit less devastating. Or if we cultivate European and Pacific partners for our agriculture exports, we won’t be as panicked if U.S. protectionism flares up.

To tie this back to the pipeline: oil and gas are among our top exports, and they’re highly concentrated in destination (mostly U.S.). A pipeline with profit-sharing is primarily about those resources. By diversifying where that oil/gas goes, Canada could reduce its tariff exposure in one of its most important export sectors. This improves overall national competitiveness because Canadian products would reach world markets more freely. Additionally, building such infrastructure can create jobs and expertise (e.g., engineering firms, pipeline technology) that strengthen our industrial base.

There is also a strategic element: Countries like Norway and Australia, which we’ll discuss next, have leveraged their natural resources to build wealth and resilience. Canada risks being the resource-rich country that didn’t fully capitalize on its potential because of internal bottlenecks and indecision. The pipeline strategy is an attempt to avoid that fate, to use our resources smartly while we still can (recognizing the world is gradually shifting to renewables over the next few decades).

Before moving on, recall how stark our current concentration is. The pie chart above showed 75% exports to the U.S. Now imagine in 10 years, that reads 60% U.S., 15% Asia, 10% EU, and 15% rest of world. That would be a healthier mix. It’s not about replacing the U.S., it will likely always be our largest trading partner given geography and history, but about hedging our bets.

And as a final note on this: tariffs are not just hypothetical. We’ve seen softwood lumber duties on and off for years; steel/aluminum tariffs in 2018; Buy American policies limiting access to U.S. projects. Canada can negotiate and retaliate to an extent, but the best shield is making ourselves indispensable and flexible, indispensable (so the U.S. thinks twice before cutting us off, because they need our goods) and flexible (so that if they do impose barriers, we can adapt quickly). Diversified export capability via pipelines contributes to both.

Norway’s and Australia’s Playbooks: Lessons for Canada

Canada is not the first country to grapple with how to make the most of natural resources while avoiding economic pitfalls. Two frequently cited examples are Norway and Australia, each offers lessons in different aspects: Norway in how to manage and invest resource wealth, and Australia in building infrastructure and diversifying markets for commodities. Let’s compare Canada’s strategy with these nations and see what we can learn.

Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund: Turning Oil into a Blessing

When Norway struck oil in the North Sea in the late 1960s, it transformed a modest Scandinavian economy into a wealthy nation. But crucially, Norway’s government didn’t simply spend all the oil money as it came in. Instead, in 1996 they set up the Government Pension Fund Global, commonly known as Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, to save and invest petroleum revenues for the long term. Today, that fund is worth about 20 trillion Norwegian kroner (≈ $1.8 trillion USD) reuters.com, making it the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, owning ~1.5% of all global stocks!

This astronomical sum, about 4 times Norway’s own GDP reuters.com, is effectively a nest egg for the nation, invested in everything from tech stocks to bonds to real estate worldwide.

Why does this matter? Because Norway’s approach tackled two key issues: inflation and diversification of wealth. By investing oil revenues abroad and only spending a small, controlled percentage of the fund each year (the fund adheres to a rule to spend only the expected real return, about 3% per year, on the national budget), Norway avoided flooding its domestic economy with too much cash. This helped prevent the kind of runaway inflation or currency overvaluation (known as “Dutch Disease”) that resource booms can cause. In essence, Norway separated the timing of earning money from spending money: they earn a lot quickly from oil, but spend it gradually over generations. Meanwhile, the investments mean the wealth is diversified into global assets, insulating it from an oil price crash. If oil prices tank, Norway’s fund might even buy stocks cheaply and gain later; if oil prices soar, the fund swells but they don’t immediately inject that into domestic spending. The result has been relatively steady economic growth, low inflation, and a massive financial cushion.

Profit-Sharing, Norwegian Style: One way to view Norway’s model is as a national profit-sharing scheme. The profits from oil (which is owned by the public there, as in Canada) are shared with all Norwegians via the fund, every citizen is, in theory, a shareholder in that $1.8 trillion pot (worth about $320,000 per person!) reuters.com. It’s not paid out as checks, but it pays for public services and future security. Canada, in contrast, has not implemented a federal sovereign wealth fund for resource revenue. Some provinces tried, Alberta set up the Heritage Fund in 1976, but it never grew remotely like Norway’s (Alberta’s fund is only about C$18 billion due to years of withdrawals and insufficient contributions). So, one clear lesson: Canada could improve by saving and investing resource profits more strategically. If the proposed pipeline is profitable, funneling a significant chunk of those profits into a fund for economic diversification or debt reduction could mirror Norway’s success. This would ensure the benefits of the pipeline last well beyond the life of the oil reserves and help future generations, especially as the world transitions to greener energy.

Another aspect: Norway’s economy today is quite competitive beyond oil. They fostered industries like shipping, fishing, telecom (think Nokia, oh wait, that’s Finland! But Norway has Equinor in energy tech, etc.), and they consistently rank high in innovation and education. By shielding their economy from the shock of too much oil money, they had space to develop other sectors. Canada’s challenge is similar, how to use current resource wealth to invest in the next economy (whether that’s clean tech, AI, biotech, etc.). A pipeline that generates revenue can be part of that story if those revenues are invested wisely (e.g., funding research, improving education, or even investing in clean energy infrastructure as a bridge).

One more Norwegian lesson: community buy-in. Norwegians broadly support oil development despite being a very climate-conscious people, because they see tangible benefits, free education, excellent infrastructure, strong social safety nets, all partly funded by oil profits. In Canada, if every province sees a direct benefit from oil pipelines (via profit-sharing), it might similarly build broader support for these projects, even in places where people are more skeptical. It turns a potentially divisive issue into a collective venture.

Australia’s Resource Infrastructure and Market Diversification: Boom to Smart Build-out

Across the globe, Australia provides another instructive comparison. Like Canada, Australia is rich in natural resources, minerals (iron ore, coal, gold) and energy (LNG, coal seam gas). And like Canada, Australia’s economy is otherwise service-oriented and diversified. How did Australia handle its resources?

In the 2000s and 2010s, Australia went through a mining investment boom to meet China’s voracious demand for raw materials. Companies (with government support in terms of policies and infrastructure funding) invested heavily in infrastructure: railways, ports, and pipelines. For example, in Western Australia’s Pilbara region, private and state investments created sophisticated networks to haul iron ore from remote mines to port facilities at astonishing volumes. The result: Australia became the world’s largest iron ore exporter and a top LNG (liquefied natural gas) exporter. They successfully opened new markets, particularly in Asia (China, Japan, South Korea, India). In fact, as of a few years ago, over a third of Australia’s total exports went to China, mainly commodities. This is higher concentration with one country than Canada has with the U.S. in percentage terms, which did come with its own risks as we’ll see. But Australia did diversify what it sells: iron to China, coal to Japan/Korea/India, LNG to Japan/China, etc. They capitalized on being in the Asia-Pacific region during a huge growth spurt in that region.

Infrastructure Payoff

Because Australia had the export infrastructure in place (ports, rail, LNG terminals), when commodity prices were high, they could ride the wave and fill ships full of product. Canada, by contrast, struggled to get pipelines approved or built in the same period. A glaring example: Australia built multiple LNG export terminals in the 2010s and is now a major gas supplier to Asia; Canada talked about LNG exports from British Columbia for years, but the first large LNG export terminal (LNG Canada in Kitimat) is only now under construction and expected mid-decade. So a lesson is timely infrastructure development matters. Canada’s pipeline strategy, if implemented, could be a case of better late than never, ensuring we don’t miss out on the remaining window of global oil and gas demand in the 2020s-2030s.

Profit-Sharing and Federal Dynamics

In Australia, natural resources are primarily under state (provincial) jurisdiction, somewhat like in Canada. States like Western Australia and Queensland reaped huge royalties from mining and gas, while states like New South Wales or Victoria (with less mining) did not. This led to internal tension, because Australia has an equalization mechanism through its GST (Goods and Services Tax) distribution. Essentially, the federal government redistributes some revenue to even out state finances. During the boom, Western Australia complained it was contributing too much to others after “sharing” its mining wealth via this mechanism. Sound familiar? It’s analogous to Alberta’s gripe in Canada about equalization, that its oil riches lead to higher contributions that get distributed to other provinces. The Australian experience shows the importance of transparent and fair formulas for sharing resource wealth. Eventually, Australia adjusted its formula to be a bit more favorable to WA. For Canada, designing a clear profit-sharing rule for a pipeline (so each province knows what it gets and why) will be crucial to avoid squabbles. We’ll propose an example model in the next section.

Handling Concentration Risk

Australia’s heavy reliance on China became a vulnerability when relations soured in 2020. China imposed tariffs or bans on Australian coal, barley, wine, and more (in retaliation for Australia’s political stances). Australia had to scramble to find new markets (e.g., coal to India and Japan, barley to Southeast Asia). They did manage to redirect a lot of trade, but not without pain, some industries took losses. The takeaway for Canada is clear: even if we open new markets, don’t let one new market become the next single point of failure. Diversification needs to be broad-based. If Canada’s pipeline sends oil to say, primarily India, and then India decides to favor another supplier, we shouldn’t be left in the cold. So the goal would be a spread of buyers, some in Europe, some in Asia. This might mean working diplomatic and trade channels to ink supply agreements with multiple countries. Basically, diversify not just away from the U.S., but among the alternatives too.

Environmental and Social Balance

Both Norway and Australia have also faced the balance of resource development vs environmental concerns and Indigenous rights (in Australia’s case, Aboriginal land rights). Norway, for instance, decided not to develop some sensitive areas and to invest oil funds into renewables abroad. Australia has had contentious episodes, like the Great Barrier Reef vs coal exports debate, and negotiations with Aboriginal communities for mining on their lands. Canada’s pipeline project would no doubt face environmental scrutiny (climate impact, spill risk) and require Indigenous consultations and partnerships. One improvement Canada can aim for, learning from past mistakes, is to ensure Indigenous communities along the pipeline route are partners in the project (some bands have pursued an ownership stake in the Trans Mountain pipeline, for example). This could be another layer of “profit-sharing”, not just provinces, but First Nations benefiting, which increases the project’s legitimacy and fairness.

Summing Up The Lessons:

From Norway:

Save the windfall, don’t inflate the economy, invest for the future, and make it so that everyone benefits (which builds public support). Canada should consider channeling pipeline profits into a sovereign-like fund or at least into debt reduction and strategic investments, rather than treating it as just another revenue to spend immediately. Also, Norway shows the power of a clear national strategy, they literally have a rule for how to handle oil money. Canada could emulate this discipline.

From Australia:

Build the infrastructure to get your resources to market while the demand is there, and be proactive in finding multiple buyers. However, guard against over-concentration in any new market. Also, address internal fairness, if one region is resource-rich, find a mechanism to share with others (Australia’s messy GST fights suggest doing so before resentment builds). And one more thing: Australia did create a Future Fund (a sovereign wealth fund) in 2006, which, while not solely from resource revenues, now stands around A$225 billion yearinreviewfy24.futurefund.gov.au. It’s smaller relative to their economy than Norway’s, but it’s something. So both peer examples have national funds; Canada federally does not. Perhaps the pipeline strategy could be the catalyst for Canada to start one.

A Fair Share for Provinces: How an Interprovincial Profit-Sharing Model Could Work

A critical component of the proposed strategy is interprovincial profit-sharing. This means that rather than all the profits (or tax revenues) from a pipeline going just to the producing region or the federal coffers, they would be shared among provinces in some agreed way. The goal is to ensure every province sees a benefit, fostering unity and cooperation on what might otherwise be a contentious project. How might this work in practice?

Let’s outline a hypothetical profit-sharing model for a transnational pipeline: Imagine this pipeline generates $5 billion in profit per year from transporting oil (through tolls/fees). Rather than that profit all accruing to, say, one pipeline company or one province, we split it up:

|

Allocation

Category |

Share of

Profit |

Beneficiaries

& Rationale |

|

Resource

Province |

30% |

e.g. Alberta,

for providing the oil resource (ensures the origin gets a premium for its

contribution) |

|

Transit

Provinces |

20% |

e.g. any

provinces the pipeline physically crosses (compensates for

environmental/social impact and land use) |

|

All

Provinces (per capita) |

50% |

Every

province gets a share based on population, so all Canadians benefit even if

they’re not on the pipeline route |

This is just one model (numbers illustrative), but it captures key principles: reward the producer, compensate the hosts, and share with everyone. Under this scheme, Alberta might get, say, 30% (1.5 billion) annually, the pipeline route provinces (Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, maybe New Brunswick if that’s the terminus) collectively split 20% (~1 billion, perhaps divided by distance or equally), and the remaining 50% (~2.5 billion) is split among all ten provinces by population (so, for instance, Ontario (38% of Canada’s population) might get ~$950 million, Quebec (23%) ~$575 million, BC (13%) ~$325 million, and so on, including provinces not on the route like BC or Nova Scotia).

Such a model means even a province like Nova Scotia or PEI, far from the pipeline, sees direct revenue, giving them a reason to politically support it. It’s akin to how federal equalization works (richer provinces indirectly support poorer provinces through federal transfers), but here it’s not about “have and have-not” status; it’s more like a dividend to all for a project deemed national infrastructure.

The profit-sharing could be administered through a federal vehicle, for example, the pipeline could be partly federally owned or taxed, and the federal government then remits the shares to provinces each year. Or it could be structured as an equity consortium of provinces (each province holds a stake in the pipeline company proportional to some formula and gets dividends). The exact mechanism can be debated, but the outcome is what matters: broad-based distribution of benefits.

Why is this so important? Canada has seen pipeline projects fail in the past due to lack of consensus, notably the Energy East pipeline was abandoned in 2017 amid regulatory hurdles and opposition in Quebec. One reason for opposition is the perception that “all the benefit goes to Alberta, while we take the environmental risk.” Profit-sharing directly tackles that: it says, if we do this, you get a cheque that can fund your schools, hospitals, or tax cuts, it’s not just Alberta’s gain. It essentially bribes (in a positive sense) every region to want the project to succeed. When everyone has skin in the game, the national interest and local interests align more closely.

This approach has precedents: in the 1950s, when Canada built the TransCanada natural gas pipeline, there were debates and deals to ensure provinces along the way benefited from access to gas and some employment. More recently, the federal government’s ownership of Trans Mountain (TMX) and promise to use its profits for clean energy initiatives was a form of sharing broadly (not by province, but by purpose, i.e., using oil money to fund something that benefits all Canadians like clean tech investment). The interprovincial profit-sharing would make it much more explicit and formula-driven.

One can even argue that confederation itself is built on a spirit of sharing. We pool tax revenues and distribute for equalization, we jointly own natural resources (the Crown ownership concept), and we backstop each other in crises (as seen in pandemic aid, for instance). A pipeline spanning multiple provinces could be seen as a confederation-strengthening project: it literally links provinces physically and economically. By sharing profits, it’s saying West and East, French and English, resource-rich and resource-poor, we’re all in this together. That kind of narrative can be powerful in securing public buy-in, especially if presented transparently (with estimates of how much each province stands to gain).

Of course, the devil is in the details. The percentages could be adjusted based on negotiations: maybe the producing province argues for more (since they also bear the price volatility risk and environmental cost of extraction), or the transit provinces want more per kilometer of pipeline, etc. But any arrangement would be more unifying than the current situation where, for example, Alberta reaps most oil royalties, BC or others sometimes only see the risks, and the federal government taxes some profits but that’s about it.

What about Indigenous communities? Profit-sharing should ideally extend to First Nations and Indigenous groups whose lands are traversed or impacted. This could be through an equity stake or a revenue-sharing agreement separate from the provincial split. Many First Nations have been advocating for ownership in pipelines as a path to economic self-determination. Including them in the profit-sharing model, say, a certain percentage off the top or within the transit portion allocated to Indigenous partners, would both honor their rights and make the project more robust (since lawsuits and opposition are far less likely if Indigenous peoples are partners and beneficiaries).

For simplicity, our table didn’t break that out, but in practice Canada could establish something like: 5-10% of the pipeline’s equity reserved for Indigenous consortia (funded perhaps by low-interest federal loans to those groups to buy in), yielding dividends for those communities. This is analogous to how some Indigenous groups now have stakes in certain pipelines or mines and receive steady income that they can use for community development.

Monitoring and conditions: To ensure the profit-sharing achieves economic diversification, one might attach some conditions or guidance on how provinces use the money. For example, the agreement could encourage provinces to invest these windfalls in infrastructure, education, or innovation (rather than, say, using it all to cut gas taxes or something counterproductive). This would echo Norway’s disciplined approach, albeit at a provincial level. Even without strict conditions, citizens in each province should hold their governments accountable: “We got this extra $X million from the pipeline, let’s make sure it leaves a legacy, maybe improved transit or a tech incubator, not just a short-term splash.”

In summary, interprovincial profit-sharing turns a pipeline from a private or regional project into a truly national enterprise. It mitigates regional jealousy and ensures that if the nation is collectively accepting the risks (environmental, climate, geopolitical) of a major fossil fuel infrastructure, the nation collectively gets rewarded. It’s economic team-building for Canada.

Key Takeaways: Building Resilience, What Canadians, Policymakers, and Investors Should Do Next

We’ve covered a lot of ground, from inflation theory to trade patterns to lessons from abroad and a profit-sharing blueprint. Let’s distill the insights into a few practical takeaways:

- Inflation: More Than Just “Too Much Money.”

Canadians have learned that inflation can come from supply problems as much as from excess money. While the Bank of Canada must keep monetary policy tight enough to maintain our 2% target (and we as citizens should expect and support that stability), we also need to tackle the supply side. Investments in infrastructure like pipelines, ports, and power grids can ease bottlenecks and make our economy more productive, acting as a supply-side brake on inflation. In short, fighting inflation isn’t only Tiff Macklem’s job, it can also be about smart nation-building that ensures goods can flow as freely as money. The pipeline strategy embodies that idea, aiming to curb cost-push inflation by improving logistics and supply capacity.

- Diversification = Resilience.

Whether you’re a Canadian consumer, a policymaker, or an investor, the principle of diversification should be front-of-mind. For consumers and investors, this might mean diversifying your own investments or skills (don’t bank your whole retirement on one company or one sector’s stocks, for example). For policymakers, it means crafting policies that broaden Canada’s economic base and trade relationships. We saw how reliant we are on the U.S., a strength in good times and a vulnerability in bad. The pipeline plan to reach global markets is one step toward diversifying trade. Similarly, governments should encourage development in emerging industries (like clean tech, biotech, advanced manufacturing) so that in 20 years, Canada’s fortunes aren’t tied so heavily to one commodity or one customer. Resilience comes from having multiple options: multiple markets, multiple industries, multiple tools to manage the economy. The opposite of concentration risk is diversification benefit.

- National Infrastructure Pays Off, If Done Right.

Big projects like pipelines, highways, or high-speed rail can be game-changers. The Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s united the country and spurred commerce. In 2025, a pipeline might not capture the public imagination the same way, but it can be just as strategic. The key is doing it right: environmentally responsibly, with inclusive benefits, and forward-looking vision. That means rigorous safety and environmental standards to prevent spills and minimize emissions. It means including provinces and Indigenous peoples as partners (profit-sharing, consultation, accommodation) to ensure broad support. And it means thinking ahead, for example, possibly designing the pipeline route as a corridor that could one day also carry CO2 for carbon capture or even accommodate hydrogen in the future, so it doesn’t become a stranded asset in a decarbonizing world. Canadians and their leaders should view infrastructure not as pork-barrel spending but as investments in efficiency and competitiveness. A dollar spent on infrastructure now can save many dollars (and headaches) later by avoiding bottlenecks and costly workarounds. Bottom line: let’s be proactive and bold in building for our future, the pipeline is one piece; a national electricity grid or 5G network expansion could be others.

- Share the Wealth to Bridge Divides.

A recurrent theme has been making sure everyone benefits. This isn’t just altruism, it’s pragmatic. When regions feel left out, national projects stall. When people feel the economy is unfair, social cohesion frays. The profit-sharing model offers a template for unity: if we want provinces like Quebec or British Columbia (which may have environmental reservations) to support a pipeline, we must show them tangible benefits that align with their values (e.g., money that can be used for green initiatives or social programs locally). More broadly, Canadians should demand fairness in how economic gains are distributed. That can take many forms: stronger social safety nets, education and training opportunities in every province, perhaps even direct dividend mechanisms from resource wealth (imagine each Canadian getting a small yearly cheque like in Alaska, that’s another model). The exact approach is up to debate, but the takeaway is clear, when we grow the pie, let’s make sure every Canadian gets a bite. It will make future economic endeavors much smoother when people trust that “we’re all going to win together.”

- Learn from the Best, Adapt for Our Reality.

Norway and Australia show two different paths with resources. Canada shouldn’t copy blindly, but we can adopt the best elements. From Norway: fiscal discipline and long-term saving of resource revenues (perhaps it’s time to create a Canadian Heritage Fund at the federal level, seeded by pipeline profits or carbon pricing revenues, to invest for the future and support the transition to a low-carbon economy). From Australia: agility in infrastructure development and aggressive pursuit of new markets (maybe Canada needs a more streamlined approval process for crucial projects, without sacrificing environmental review, so we can actually build things in a timely fashion). For investors specifically, these lessons mean there’s opportunity in sectors that facilitate diversification, e.g., companies building infrastructure, or those in industries Canada wants to grow beyond resources. Policymakers should also consider the cautionary tales: avoid getting addicted to resource booms (Australia had to cut spending when commodity prices fell), and avoid complacency (Norway continually plans for a post-oil future even as it profits from oil today).

To conclude, Canada’s proposed transnational pipeline with profit-sharing is more than just a piece of energy infrastructure. It is a microcosm of how we can address larger issues: by keeping an eye on both macro-economics (controlling inflation, balancing trade) and micro-economics (fair distribution, efficiency in delivery). It blends supply-side logic (improve capacity, lower costs) with nation-building ethos (share benefits, strengthen unity). Whether or not this specific pipeline comes to fruition, the conversation around it has underscored key economic truths.

As Canadians, we should remember that inflation can erode our wealth silently if we don’t stay vigilant, and that combating it is not just about interest rates, but also about ensuring plentiful, affordable supply of the things we need. We should recognize that diversification is our economic safety net, as individuals and as a country, we prosper by not being overly dependent on any single partner or product. We should push our leaders to invest in Canada’s productive capacity, from pipelines to digital infrastructure, because that’s how we remain competitive and raise living standards in the long run. And finally, we should insist on inclusive prosperity: if we take on national projects or policies, the gains should be broadly shared, so that we move forward together.

The pipeline strategy encapsulates these ideas: it’s about moving oil, but also about moving Canada’s economy forward. It aims to keep prices stable, markets open, and people united. That, in essence, is the atomic idea at the heart of this essay: by smartly leveraging our resources and sharing the rewards, Canada can build a more inflation-resistant, diversified, and competitive economy for all.

Interactive reflection: Next time you fill up your car or pay your heating bill, consider the journey of that energy. How might a new pipeline change the story, could it lower the cost, who would it benefit, what risks and rewards does it carry? And beyond energy, what “pipelines” (literal or figurative) does Canada need to secure your economic future? These are the kinds of questions we should all be asking as we navigate the complex but opportunity-rich road ahead.

Reference Links

- "Milton Friedman's Inflation Theory Explained" - (https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/inflation.asp)

- "Canada’s Inflation Data" - (https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/indicators/key-variables/inflation-rates/)

- "Canada GDP Composition & Growth" - (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240930/dq240930a-eng.htm)

- "Canada’s Export Distribution and Trade Dependency" - (https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/start)

- "Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund Overview" - (https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/)

- "Australia’s Resource Infrastructure Investments" - (https://www.austrade.gov.au/)

- "Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Project" - (https://www.transmountain.com/)

- "Government of Canada Energy Data" - (https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/)

- "Australia's Future Fund" - (https://www.futurefund.gov.au/)

- "Western Canada Select Oil Pricing Information" - (https://www.oilprice.com/)